Global research shows that cities are not taking advantage of the full potential of nature-based solutions

A study carried out by the Basque Center for Climate Change (BC3) and the University of Almeria, with the participation of Ikerbasque researcher Marta Olazabal and Unai Pascual, identifies critical strategies to advance the application of nature-based solutions in the adaptation of cities to climate change.

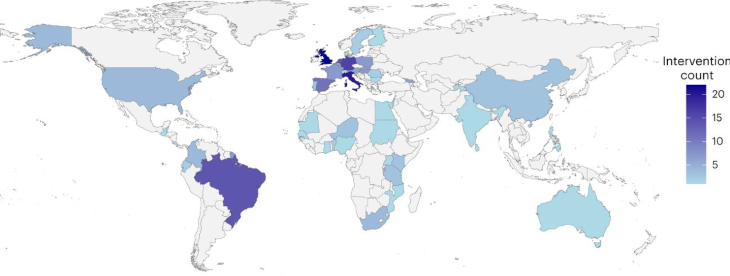

The study, published in the prestigious journal Nature Sustainability, uses data from 216 projects implemented in 130 cities around the world.

Nature-based solutions (NBS) have been identified as a critical strategy for achieving the ambitious global goals of mitigating and adapting to climate change, as well as halting and reversing biodiversity loss. Proponents highlight the ability of BNS to influence each of these areas, generating cascading benefits for both human well-being and ecosystem health. This idea of a “climate-biodiversity-society” (CBS) nexus is reflected in the recently published joint report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Nature-based solutions (NBS) have been identified as a critical strategy for achieving the ambitious global goals of mitigating and adapting to climate change, as well as halting and reversing biodiversity loss. Proponents highlight the ability of BNS to influence each of these areas, generating cascading benefits for both human well-being and ecosystem health. This idea of a “climate-biodiversity-society” (CBS) nexus is reflected in the recently published joint report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Research by the Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3), Ikerbasque and the University of Almeria, led by BC3 researcher Sean Goodwin and published in Nature Sustainability, shows how the application of BNS at a global level directly influences the “climate-biodiversity-society” nexus and how they are promoting real long-term change when used to help cities adapt to climate change.

The first conclusion of this study is that projects using BNS need to pay more attention to how to address context-specific “climate-biodiversity-society” challenges. The study shows that only 2% of the SbN studied took into account how future climate change impacts will affect the SbN themselves. As Ikerbasque BC3 researcher Marta Olazabal explains: “As they are solutions based on natural processes, the type of plants used in the context of BNS are as vulnerable to climate change as people. Therefore, in order to provide benefits in the future, BNS must be designed to be resilient to changing climatic conditions. For example, species need to be resilient to higher temperatures or drier conditions in certain locations.

Vulnerability to climate change can and should be reduced in multiple and complementary ways through BNS. In this study, however, the authors found that current BNS are primarily designed to reduce exposure and do not work from other climate vulnerability angles. For example, in most cases BNS attempt to reduce exposure to climate hazards by diverting heavy rainfall to avoid flooding (e.g. flood parks). In the future, BNS should address the needs of urban dwellers to develop their own adaptation strategies in their homes and cities (e.g. storing water for use when there is a shortage) or try to reduce the impacts of hazards (e.g. helping to cool houses and flat blocks).

The findings of this study point to the fact that people should be at the centre of BDS design. In that sense, the authors of this study have concluded that the consideration of social issues is uneven among the BDS projects analysed, as, while most of the NbS consider some form of social justice in their design, in most cases these are superficial stakeholder consultations. Only 28% of projects showed a real commitment to diverse (and marginalised) values in the implementation of the BNS, and only 20% gave explicit consideration to ensuring that the benefits (and burdens) derived from the BNS were fairly distributed. In terms of project governance, around 80% of all projects were financed and implemented by public bodies, mostly municipal governments, further highlighting the long-term vulnerability of BDS, as they are subject to changing government priorities and budgets.

Another aspect that has been analysed in this study has been the capacity of NbS to create real or transformative long-term change in these cities. They have analysed the impact of BDS projects on the city’s ecological system, society and infrastructure and concluded that less than 15% of the projects show transformative capacity in any of these dimensions. The authors attribute these trends to a lack of social engagement (beyond superficial public consultations).

The authors attribute these trends to a lack of social engagement (beyond superficial public consultations), a piecemeal approach to improving urban biodiversity conditions, or limited project connection to citywide urban planning. It is worth mentioning that these trends differ regionally, with BDS in Latin American and African cities leading the way in terms of ecological and social transformation.

The second recommendation relates to the types of information that can be used to make a systematic study of this magnitude. The information that served as the basis for this analysis came from various databases containing information on BNS projects from around the world. In the words of the study’s lead researcher and author Sean Goodwin: “In our work, it was important to include information from a variety of viewpoints worldwide, not just the Global North, so these databases have been our best opportunity to capture a greater diversity of regional information than has been done before”. However, it should be noted that 63% of the projects in these databases are from Europe alone, and as the authors of this study state, it is important to include information that captures different points of view at the global level. Therefore, in the future, more support is needed to ensure that critical contextual information showing a diversity of local conditions and experiences is not lost.